To Western eyes, the monk, increasingly,

is a figure of yesterday, and the commonest images of him are of the

kind to make easy the patronizing smile, the confidently dismissive

gesture, or that special tolerance extended to the dotty and the

eccentric. Around Friar Tuck, with his cheerful obesity, and Brother

Francis, harming no-one as he talks to birds and animals, vaguer ghosts

manage to cluster, gaunt, cowled, faintly sinister, eyes averted or

looking heaven-wards, a skull clutched in a wasted hand, with gloom

arising, and laughter dead.

Somewhere in the background there are

bells and hymns, and psalms chanted well after midnight; and, as if to

confirm that these are only the leftovers of a past surely and

mercifully gone, there is the dumb presence of all those European

monasteries visited for ten scheduled minutes during a guided tour, or

else sought out on warmer evenings by courting couples.

But for Christians, that is, for someone

who believes that there is a God, that God has manifested Himself in

historical surroundings in the person of Christ, and that insights and

obligations are thereby held up to everybody, the monk cannot easily be

shrugged off…

A linguistic usage, so long

employed by Christians that it has the look of being quite simply

“natural” surrounds the individual monk with a wall of venerable words, a

wall more solid and endurable than any that may set the boundaries of

the area where he actually lives. For the talk is of “withdrawal” from

“the world”, of “renunciation”, of a “monastic life” in contrast with

the way other people happen to live, of being “apart from”, “away from”

the rest of mankind, of pursuing a “dedicated” and “consecrated” path.

And this language, with its emphasis on the difference between the monk

and all others, very quickly begins to generate something more than a

set of descriptions. It begins to imply a value system, a yardstick of

achievement and worth until at last, and not surprisingly, there grows

the irresistible urge to speak of a “higher”, “fuller”, and “more

perfect” way of life…

Given those circumstances, it is

reasonable to wonder how a Christian may now cope with the vast

literature to which he is heir. It is also reasonable to anticipate that

he will approach it with something less than automatic deference. And

amid all the competing voices, his capacity to deploy a commitment and a

sustained interest may well diminish as he strives to assemble for

himself and for his friends criteria of evaluation that make some kind

of accepted sense. How, for instance, is he to approach a work like The

Ladder of Divine Ascent by John Climacus?

The setting at least can be

readily established. The Ladder is a product of that great surge of

monasticism which appeared first in Egypt during the third century,

spread rapidly through all of Christendom, and eventually reached the

West by way of the mediating zeal of figures such as John Casssian. The

general history of this most influential development in the life of the

early Church is well known, even if details and certain interpretations

continue to preoccupy scholars, and there is no need to attempt here a

sketch of what has been so well described by others…

That many of the first monks had

glimpsed a connection between the experience of hardship and an enhanced

spirituality is evident in the writings of the early Church. And in the

neighborhood of that perceived connection were other sources of the

resolve to enter on a monastic life. There was, for instance, the belief

that, given the right conditions and preparation, a man may even in

this life work his passage upward into the actual presence of God; and

there, if God so chooses, he can receive a direct and intimate knowledge

of the Divine Being. Such knowledge is not the automatic or the

guaranteed conclusion of a process.

It is not like the logical outcome of a

faultlessly constructed argument. There is no assurance that a man will

come to it at the end of a long journey. But to many it was a prize and a

prospect so glittering that all else looked puny by comparison; and,

besides, there were tales told of some who, so it seemed, had actually

been granted that supreme gift of a rendezvous…

There is now in the consciousness

of the West a terminology and set of value judgments centered on the

person. From the era of the Renaissance and the Reformation up to the

present time, there has been a steady progress in the insistence on the

reality and the inherent worth of the individual. Some philosophers, of

course, would argue that man the word-spinner has in this merely

demonstrated once again his capacity to sublimate reality and has only

succeeded in hiding from himself that he is no more – and no less- than a

very complex organism.

But this is not a widely shared view.

Instead, there is much talk of human rights, of one man’s being as good

as another, of the right of the poor to share in the goods of the world,

of one-man-one-vote. What all this has done to a belief in God is a

theme of major import. However, on a more restricted plane, a difficulty

for anyone today reading The Ladder of Divine Ascent or similar texts

is that in these a somewhat different view of the person is at work. If

modern Christianity has invested heavily in the notion of the value of

the individual person, it has been at the cost of a seeming

incompatibility with much that was felt and believed in the early

Church.

Still, whether incompatible or not with the modern sense of the self and of identity, The Ladder of Divine Ascent

remains what it has long been, a text that had a profound influence,

lasting many centuries, in the monastic centers of the Greek-speaking

world. As such it deserves at least a hearing, if only to ensure that

the awareness of the Christian past is not impoverished…

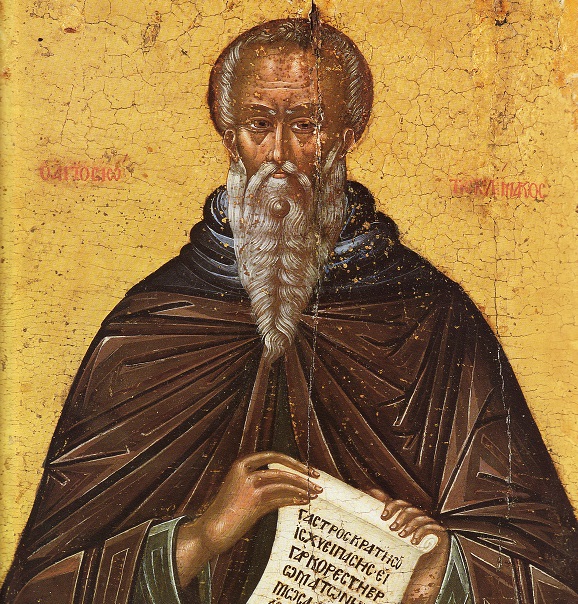

Hardly anything is known of the

author, and the most reliable information about him can be summarized in

the statement that he lived in the second half of the sixth century,

survived into the seventh, passed forty years of solitude at a place

called Tholas; that he became abbot of the great monastery of Mount

Sinai and that he composed there the present text. The Ladder was

written for a particular group, the abbot and community of a monastic

settlement at Raithu on the Gulf of Suez. It was put together for a

restricted audience and to satisfy an urgent request for a detailed

analysis of the special problems, needs, and requirements of monastic

life. John Climacus was not immediately concerned to reach out to the

general mass of believers; and if, eventually, the Ladder became a

classic, spreading its effects through all of Eastern Christendom, the

principal reason lay in its continuing impact on those who had committed

themselves to a disciplined observance of an ascetic way as far removed

as possible from daily concerns…

John Climacus is concerned not so

much with the outward trappings of monasticism as with its vital

content. To him the monk is a believer who has undertaken to enter

prayerfully into unceasing communion with God, and this in the form of a

commitment not only to turn from the self and world but to bring into

being in the context of his own person as many of the virtues as

possible. He does not act in conformity with virtues of one kind or

another. Somehow, from within the boundaries of his own presence, he

emerges to be humility, to be gentleness, to be sin abhorred, to be faith and hope and, above all else, to be love…

Influential texts, of course,

have a life and season of their own. They supply the dominant themes of

an era, acquire eventually the status of the honorably mentioned and the

unread, emerge once again to promote undreamed-of perceptions, and

slip, perhaps forever, out of sight and out of reckoning. But in a time

of rapid change, such as today, even the capacity to ponder or to

remember can be so blunted that not only will an individual work sink

from view, but the very realm it opened up, the vein it disclosed, will

also disappear, leaving men with an impoverished vision and a diminished

grasp of the available images and ideals from which to construct for

themselves a worthwhile sense of meaning and purpose.

To lose an awareness of the choices on

offer, to be locked without respite into a single, all-pervasive bias,

is a disaster. This much at least is clear amid the unfinished history

of the twentieth century, with its countless grim examples of unsheathed

bigotry, rampant prejudice, and dreadful unreason. But in the meantime

there is still the influential text, like some shining life, presenting

as does The Ladder of Divine Ascent one of the many opportunities

to confront a view of being and of man. And if the fruit of such a

confrontation is a researched “No”, or a reasoned acquiescence, then

indeed the sum of human enrichment can confidently be held to have been

augmented.

Colm Luibheid, Preface to John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, Paulist Press 1982.